This post, admittedly, has nothing to do with sailing, cruising, or any of the various catastrophes we have brought upon ourselves. Instead, let’s talk about doctors. Since I, Bob, happen to be one, it’s a subject near and dear to my heart. I did the whole traditional medical training thing: college, then med school at the University of Rochester, then a pediatric residency training program at Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital in Cleveland. What I have discovered, on our journey through the Caribbean, is that there is a whole other system for producing doctors that practice in the States. Namely, Caribbean Medical Schools.

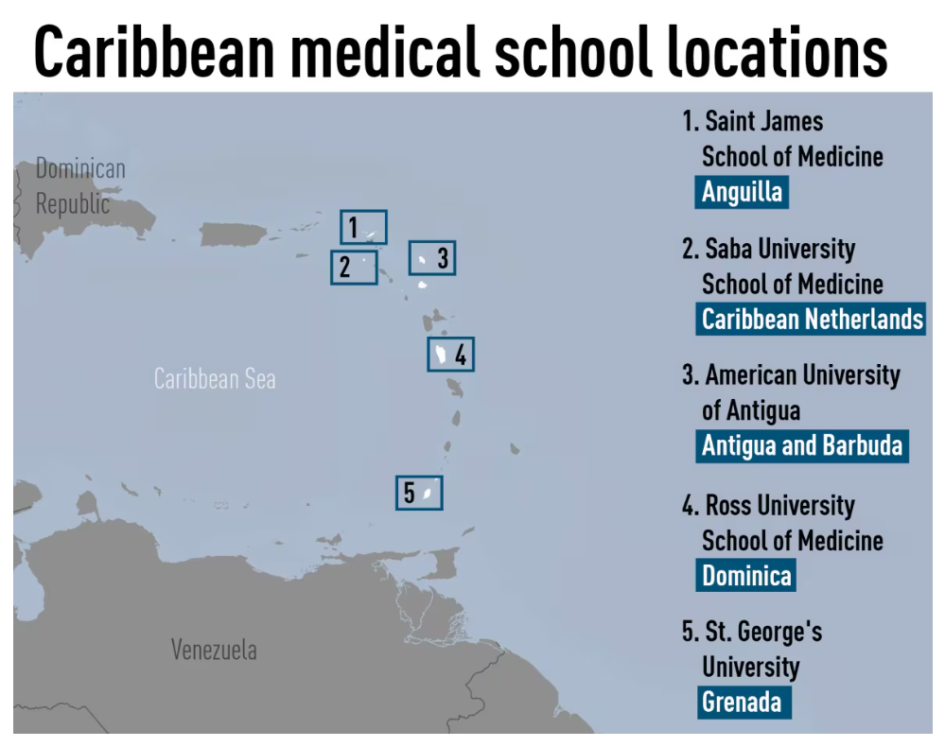

The Caribbean as a region has a total population of about 44.4 million people. These people live on the islands stretching from The Bahamas, to Cuba, to Hispaniola (Haiti and the Dominical Republic), to Puerto Rico, and down through the smaller islands to Trinidad. Scattered across those islands are about 80 medical schools. Yep. Eighty. Now, of these, about 15 are in Cuba, so let’s eliminate those, leaving us with 65 medical schools. Medical schools in the Caribbean are divided into two types: Regional and Offshore. Regional schools train doctors for work in the Caribbean region-students who live and plan to work in the Caribbean. Offshore medical schools cater, usually exclusively, to students from the United States and Canada who plan to practice in North America. There are 28 regional medical schools outside of Cuba, leaving about 37 medical schools in the Caribbean training doctors from the US and Canada. That’s a lot of medical schools for a few islands. For instance, Aruba has 5 such schools. Barbados has 8. Why? Well, it comes down to, as most things do, money. These schools are private, for-profit operations. The total cost of getting an MD from one of these schools can run about half a million dollars, including living expenses. It is BIG business for these companies. For example, St. George’s University School of Medicine in Grenada claims that it places more doctors into residency programs in the US than ANY OTHER MEDICAL SCHOOL IN THE WORLD (including the US medical schools)! It’s enrollment is over 5,000 students for the four-year program. Of course, the students are only in Grenada for the first two years, which consists of classroom learning. For the second two years, students go abroad to the US or Canada for clinical rotations. The medical schools pay hospitals to take their students, further upping the costs (I read an article stating that St. George’s pays $100 million to stateside hospitals for clinical rotations. Plus, students have to pay to live where their rotations are.

So who’s paying this? Typically, Caribbean medical schools are “second-chance” schools. The students are those who were unable to gain admission to a US medical school, usually due to borderline academic performance.

And this is where the “buts” start to come in.

St. George’s and some of the other top Caribbean schools claim they have placement rates over 95% into US residency programs. And that may well be true. What they don’t mention is that only about 65% of students graduate after 4 years. Add an extra year and the graduation rate is about 80%. That means that one in five students is washing out, saddled with a large amount of tuition debt. A cynic might say that these schools have lower admission standards because they want the money from students they know won’t complete the program. There is no incentive to turn applicants away. In fact, admission rates are far, far higher than for schools in the US. A cynic might further say that the schools have an incentive to weed out any students they don’t think can match into a residency program because it will hurt their statistics. After collection a year or two of tuition, that is. Some students say “It’s easy to get in, but hard to get out.” Those students who do finish tend to have extremely high debt burdens: in excess of $400,000. I ask you: if you have that kind of debt to pay off, are you going to gravitate towards a lower-paying specialty like primary care? Doubt it.

I am not in any way suggesting that doctors trained abroad are substandard. I am sure many of them are excellent physicians. And the fact that there are so many residency slots available to the graduates of these programs demonstrates that the US is not training enough doctors on its own soil. But the answer to that physician shortage perhaps doesn’t need to be a system that squeezes students for large amounts of cash by programs that don’t have a vested interest in helping all of their students succeed.

And now back to our regularly scheduled programming.

August 25, 2024 at 5:47 pm

Rey interesting, Bob. Thanks for sharing that.

My niece, a pediatric urologist, finished med school w/ about $250,000 of debt. She went to St. Louis U med school (private).

August 28, 2024 at 2:14 pm

Yeah, it’s expensive no matter how you slice it.

August 25, 2024 at 5:47 pm

Very interesting—typo

August 26, 2024 at 2:09 pm

Thanks for the info Bob. Well said.

August 28, 2024 at 2:14 pm

Thanks, Craig!

August 30, 2024 at 4:41 pm

One of my favorite parts of cruising (and traveling in general) is learning how systems work in other countries, especially education and skills training. The US doesn’t have a monopoly on good practices, and seeing how other countries do it is fascinating. Seems like the US also doesn’t have a monopoly on the for-profit schools taking advantage of a tough situation for students.